By Matt Thompson, NTN Development Coach, August 2021

In the course of my work, I’m fortunate to have the opportunity to consistently think with and learn from some inspiring educators in schools and districts that are tackling innovative work. And that work is hard too. Increasingly, I wonder if one thing that makes that work hard is that we are thinking about and/or acting on different understandings of “learning”?

It seems obvious that educators might talk about learning a lot and work to get aligned in that conversation, but I don’t believe that’s the case, for a range of reasons. Working from inconsistent understandings of “learning” leads us each to act on the same idea or change effort in inconsistent ways, limiting what’s possible for those that are to do the learning.

So consider this an invitation to a conversation about learning, possibly with others or maybe just a good chat with yourself. The act of writing this, getting lots of good feedback, revising, rewriting, etc. has already kicked up some needed conversation and reflection for me. I hope it does for you too.

Let’s start with this video, and perhaps you have seen it already.

When conditioned to pay attention to one set of details, how easy was it to miss other details?

“Like a pane of glass framing and subtly distorting our vision, mental models determine what we see.” (Senge, Roberts, Ross, Smith, & Kelner, 2009, p. 235)

I find that analogy of a “pane of glass” quite useful when considering mental models, and will stick with it here. The longer we look through that unique pane of glass, the less we consciously think about the glass itself and what it frames. Peter Senge, in his work on Systems Thinking, discusses the idea of mental models, which are deeply ingrained assumptions and generalizations that influence how we understand the world and take action in it. (Senge, Roberts, Ross, Smith, & Kelner, 2009)

Two people holding different mental models can process an event or idea in entirely different ways. A simplified example of that is how two pedestrians, one American and one British, might approach crossing a busy street in London with two different sets of operating assumptions about how traffic flows. The American has spent a lifetime situated within a set of agreements and rules about which side of the street cars drive on. Based on that conditioning, the American in London needs an explicit nudge (i.e. “Look right!”) to pause and re-examine her pane of glass in order to make better decisions.

MENTAL MODELS IN EDUCATION

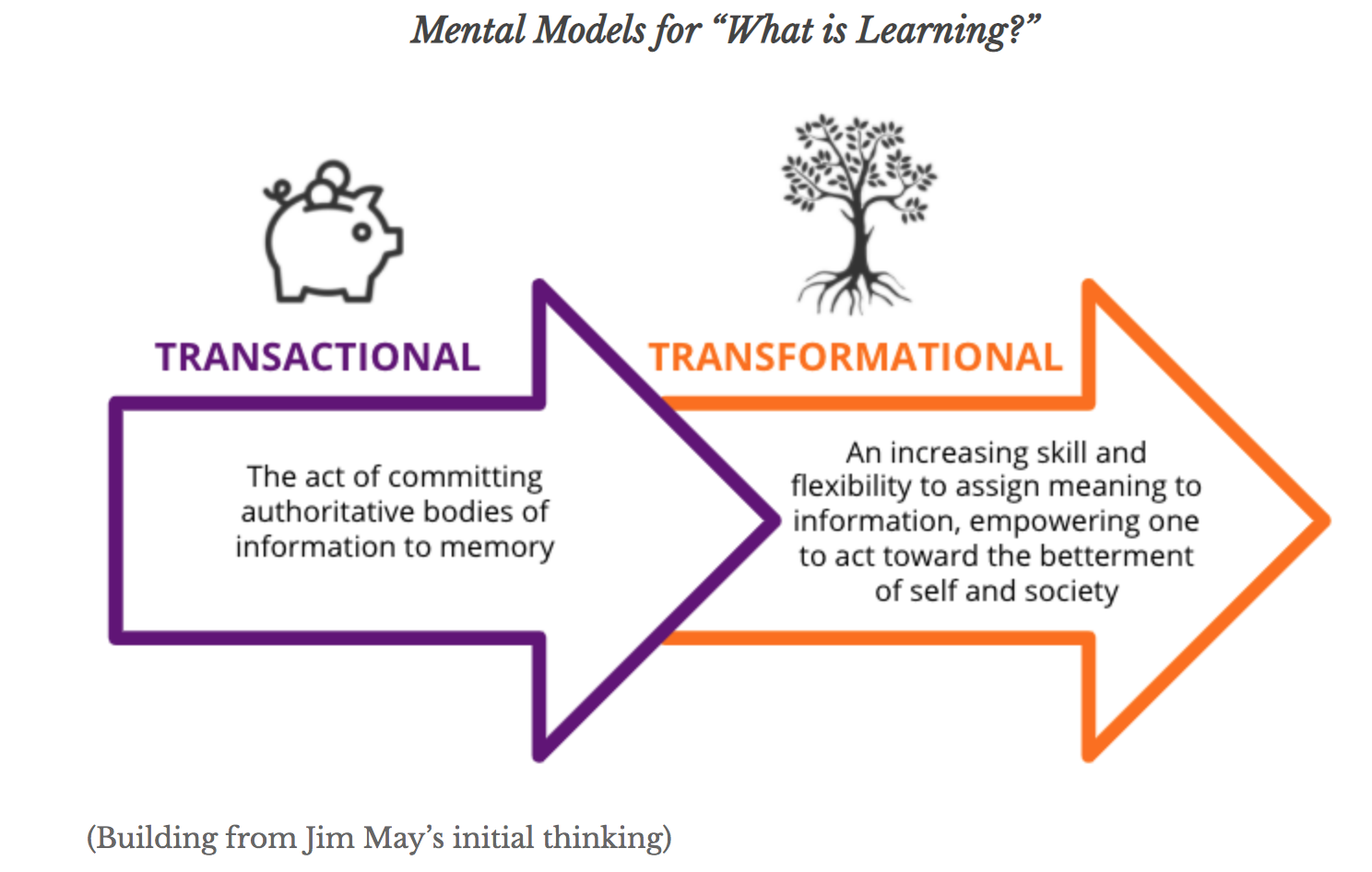

The mental models educators hold about learning greatly influence what happens or not in their classrooms and schools. In my experience of working with schools and districts around the country, educators generally operate from one of two mental models about learning:

Mental Models for “What is Learning?”

(Building from Jim May’s initial thinking)

The Transactional mental model for learning operates from one set of assumptions, while the Transformational mental model for learning operates from a different set of assumptions. There are certainly degrees between and around these two mental models, and I find most educators and policymakers predominantly operate from one or the other. And depending on your mental model for what learning is, that pane of glass then frames your thinking on how people learn, and as a result, what school should look like.

MENTAL MODEL #1 – TRANSACTIONAL LEARNING

Traditionally, schools and classrooms have been centered around this definition of learning, where students are expected to commit authoritative bodies of information to memory and teachers are expected to get that information to the students. That’s the exchange, hence the label for Mental Model #1 – Transactional Learning. This mental model can lead to more passive student experiences where the learning ends with singular right answers. A classroom example is 1) listen to the lecture and look at the slides, 2) fill out the worksheet with the answers, 3) get a grade on what you got right and wrong, and 4) repeat.

The Transactional Learning mental model is attractive, and possibly addictive, because it is easy to measure at small and large scales. As a result, education policymakers and standardized test creators have and continue to look predominantly through the Transactional Learning pane of glass. The decisions made from this mental model by policymakers cascade down and shape the mental models about learning for districts, schools, and the individuals inside them. Schools pushing in directions contrary to Transactional Learning often find themselves facing systemic headwinds that pull them back to how things “ought to be.”

In my experience, this mental model for learning often encourages quantitative, rather than qualitative, responses when the outcomes are deemed insufficient. It responds with more rather than different, often putting the burden on the learner to get more out of the transactional experience. That looks like adding an additional period of math for a struggling learner who did poorly on an interim test, thus adding more time for math but continuing with the same set of assumptions about how learning happens (or not in this case). While more time can certainly help, our mental model for learning will influence how we choose to structure the time for learning that we have.

A sole focus on the learning “transaction” misses the opportunity to investigate what else might be needed in the learning experience for a student to advance their understanding of a concept or skill. As Hattie and others have argued, there is a role for surface learning experiences in the overall learning journey, but, on its own, Transactional Learning just doesn’t go far enough. (Hattie & Donoghue, 2016)

TRANSACTIONAL LEARNING AND INEQUITY

The history of Transactional Learning shows a consistent effect of oppressing those at the margins. That’s not been accidental. One way this happens is through limiting opportunities for students to engage with a thinking curriculum.

As an example, Samuel Armstong, Booker T. Washington, and others aimed to produce a Black working force post-slavery, and they viewed schooling through this limited pane of glass for learning. While it certainly was radical coming out of slavery, Black youth were to be steered toward the trades and the industrial arts, without access to intellectual pursuits. This conveniently supplied northern industrialists with a relatively skilled labor force less able to interrogate the unjust system they were situated within. This also promoted a view of Black Americans as racially inferior and effectively tracked who ended up where in the resulting social and working hierarchy. (Nelson & Williams, 2018) This history of Transactional Learning points at those in power using that power to determine what is to be learned and by whom, with the ultimate goal of maintaining the hierarchy.

We see the same story today as a disproportionate number of poor kids and students of color struggle in under-funded and under-resourced schools that can’t and don’t offer the same rigorous instruction offered in more affluent and whiter schools. (Noguera, Darling-Hammond, Friedlaender, 2015)

Fortunately, there is also a long history of critique, in both word and practice, of this narrow mental model for learning.

Along with others, W.E.B. DuBois challenged Transactional Learning views and schooling being designed with that mental model. Paulo Freire, in his seminal book Pedagogy of the Oppressed, labels this the “banking” concept of education, with teachers as depositors and students as the containers to be filled (Freire, 1972). As educators have consciously and subconsciously adopted and operated from a Transactional Learning mental model, schools and classrooms have replicated oppressive society as a whole, dehumanizing the learner in the learning process. (Haberman, 1991)

While “dehumanizing” may feel like a strong word initially, consider what happens to the motivation and zeal for learning as a typical 5-year-old progresses through public schooling to an eventual high school graduation. Positioning the learners as passive recipients in the learning process, Transactional Learning fails to acknowledge the inherent curiosity, desire, social needs and cognitive needs of the learner, who must be empowered in that process.

Historically, education has primarily been viewed through the Transactional Learning pane of glass, which has then framed the structural, political, cultural, and instructional choices made about learning, including who has power and who doesn’t, in and beyond the classroom. This is the school we likely went to ourselves, and it is deeply woven into a subconscious act of replicating “how we do things around here.” Improvement efforts come and go, but the underlying Transactional mental model holds on tight. That’s the rub with mental models, they become deeply ingrained (Senge, Roberts, Ross, Smith, & Kelner, 2009), and we actually fail to realize the pane of glass has distorted and limited our view, yet we remain stumped by the dogged and disappointing outcomes.

The Transactional Learning mental model for learning, on its own, is wholly inadequate for serving our kids and communities. The data has proven that out over and over again. Thankfully, there’s another, more expansive mental model for learning that we can operate from.

MENTAL MODEL #2 – TRANSFORMATIONAL LEARNING

One of my favorite moments in Project-Based Learning occurs at the moment of “transfer.” It’s that moment when, after posing some good questions and getting some good scaffolding, the students attempt to transfer a new understanding to an authentic problem. That’s where the rubber meets the road, or not. How nimble is that student’s understanding of the concept? Is their grasp of the idea flexible and adaptable enough to apply it toward a meaningful problem? It can also be wonderful when those transfer attempts don’t go so well, and then students ask even better questions about the targeted idea…the deeper questions they didn’t initially realize they needed to ask.

A version of this plays out for me fairly regularly with home repair. It goes something like this:

Something goes wrong with the house (often that’s water going where it shouldn’t).

I poke around to see if it’s a familiar problem, and often it isn’t. This kicks off a series of questions for me.

I head to Google with my questions, which then offers up some scaffolding for me, usually in the form of a YouTube video of someone more skilled doing a similar repair.

After a trip to Lowes for needed supplies, I take my first attempt at the fix – this is that moment where I attempt to “transfer” my understanding from the video towards my specific problem. This almost always helps me realize that I missed something I should have paid more attention to in the YouTube video.

I go back to the video with my additional questions, possibly search for another video, or, if still stuck, will call up someone who has possibly tried this repair (my Dad, Father-In-Law, or a handy friend).

I then go back for another “transfer” attempt to fix the issue. If all goes OK, I make some version of a repair that lasts for a while!

The above process matters because when the same or similar issues inevitably go wrong with the house again, the previous learning experience has equipped me to do better. The scaffolding can be removed because I’ve learned something deeply enough to continue applying it.

THE SCIENCE OF LEARNING

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, in their book How People Learn II: Learners, Contexts and Cultures, describe learning in this way:

“Learn” is an active verb; it is something people do, not something that happens to them. People are not passive recipients of learning, even if they are not always aware that the learning process is happening. Instead, through acting in the world, people encounter situations, problems, and ideas. By engaging with these situations, problems, and ideas, they have social, emotional, cognitive, and physical experiences, and they adapt. These experiences and adaptations shape a person’s abilities, skills, and inclinations going forward, thereby influencing and organizing the individual’s thoughts and actions into the future.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

Mental Model #2 offers an alternative pane of glass to look through – a framing and view for defining learning that is consistent with the science of how people learn. While the Transactional Learning model ends with attempts at depositing information into the student, a Transformational Learning mental model promotes learning as the active endeavor we know it to be. This model for learning assumes that the learner must develop an ability to assign meaning to the information, and then use that new understanding to make new, better decisions for themselves and society. There, again, is that important “transfer” moment. What good is knowledge if it is unable to find traction beyond a multiple choice test?

When looking through this pane of glass, the framing and view is much different than a Transactional view of learning. Decisions made from a Transformational Learning mental model point to very different classroom experiences, where students are asked to advance surface understandings, and to use information and meaning to engage complex, meaningful problems. The added questions of “what can you do with that understanding?” and “what has that new understanding done to you?” distinguish this from a Transactional mental model. Both the learner and the learner’s surrounding environment are Transformed as a result of the learning process.

INTERROGATING OUR MENTAL MODELS IN THE CONTEXT OF HISTORY

Post-slavery, some northern whites wanted to “save” former slaves through education and saw the need to “civilize” Black people into white culture via the creation of schools. They centered a Transactional model for learning, combined with blatant racism (the two often go hand-in-hand). Power and authority over knowledge was to be held by the white teachers and policy makers. (Nelson & Williams, 2018) In essence, they were creating the distorted pane of glass by which learning was to be viewed and framed.

Where Transactional mental models have been consistently effective in generating inequitable outcomes by race and class, Transformational Learning provides fertile ground for pedagogies that intentionally disrupt traditional power dynamics in school and beyond, situating the learner to think as an active and collaborative inquirer in pursuit of understanding. And that shift produces outcomes that matter.

Historically, resistance to Transactional Learning and its applications for schooling came from many. The African Methodist Episcopal church sought a more humanizing model for schooling, designed and run by Black educators, that empowered Black youth to interrogate the injustices of the past and create a better future. (Butler-Mokoro, 2010) DuBois later followed with his push to move on from the narrow, vocational education focus for Black youth to higher pursuits for rigorous learning. The Black literary societies of the 19th century moved beyond literacy as a limited set of atomized skills and proficiencies to a more expansive view of literacy grounded in its applied power for action and liberation. (Muhammad, 2020)

It’s important to recognize the perils and depth of the fight by the Black community, post-slavery, for a more just, rigorous education inclusive of the intellectual thought promoted by Transformational Learning. During this quest for a more intellectual and ambitious view of learning from 1866-1872, an estimated 20,000 people, both black and white, were killed because of the fear of a rightfully educated Black person. (Nelson & Williams, 2018)

We must see learning in its fullest possibility, as resistance to that unjust past and the inequitable outcomes that continue to plague public schooling. Learning must be inclusive of Equity Pedagogy’s environments in which “students can acquire, interrogate, and produce knowledge and envision new possibilities for the use of that knowledge for societal change.” (McGee Banks & Banks, 1995, p. 153) Through leveraging student inquiry to engage authentic problems in our communities via Transformational Learning, students are supported to develop job-ready AND democracy-ready skills and mindsets in the process.

This points at a more expansive purpose for school, enabled by a Transformational Learning mental model. Beyond just helping kids graduate and get jobs, which is important, this mental model for learning also must equip young people to lead and engage intellectually in a multicultural democracy. The rich, intellectual traditions of the Black community have pushed for this view of learning. It is a markedly different pane of glass by which to view learning and schooling, one where school is much more than a place to passively take in information and gain a few job skills. (Perry, 1993)

Transformational Learning requires a learning process to practice what it preaches by rebalancing power more equitably in schools and classrooms. AND, in its fullest ambition, it develops students that can then enact the needed changes to rebalance power equitably in our society. In other words, Transformational Learning emphasizes both how you take the learning journey AND the outcomes the journey fosters.

MENTAL MODELS AND SCHOOL INNOVATION

Many efforts at Transformational Learning practices like Project-Based Learning (PBL) fail before they get started. This might happen when a district leader or school board member is drawn toward the look and feel of the PBL instructional approach. As the school attempts to scale those instructional efforts, the people and system continue to operate from a Transactional Learning mental model for everything else. Confusion and frustration reigns as Transformational Learning efforts run into a school/district system and culture designed for a different purpose of school and a different understanding of what learning is. Specific examples of this conflict include:

7-8 period-days of 45-50 min classes vs the 75+ minutes needed for deeper learning

Excessive interim testing on lower order thinking that eats up a lot of time and limits opportunities for teacher autonomy to design meaningful inquiry-based experiences

CTE certifications held as a higher priority than developing strong readers, writers and critical thinkers

I often hear educators I’m working with report doing some “traditional” teaching when taking a break from efforts at PBL. And that always gives me pause, because “traditional” teaching that centers a Transactional Learning mental model has proven over and over to be ineffective and harmful. It turns out that a lot of “tradition” in our public schooling system sucks.

I recognize that committing to look at everything through a Transformational Learning “pane of glass” requires work. History and research tell us that work is a necessity, though the work becomes efficient and effective as the school and district system become more aligned around a shared Transformational Learning mental model.

And that effort doesn’t have to look like a full-blown PBL experience every minute. Transformational Learning also has to live in the daily moments too, and can be applied to a single topic or concept. Thankfully there are well-established daily practices, protocols, and thinking routines that position students as active sense-makers and involve them in meaningful discourse with one another.

I get the pleasure of learning from some brilliant educators who have deeply internalized a Transformational Learning mental model. Whether it’s through ambitious community-based PBL experiences, a thoughtful Socratic Seminar, or an intentional round of peer feedback, these educators clearly look at learning through the Transformational Learning pane of glass. And, once you have spent time looking through and experiencing that Transformational Learning mental model, it then becomes deeply ingrained…and there’s no going back. These educators have internalized not just the argument for Transformational Learning based on the science of learning, but also planted themselves firmly in the equity imperative of Transformational Learning too.

LEARNING OUR WAY FORWARD

The systems thinker, Donella Meadows, said “Your paradigm is so intrinsic to your mental process that you are hardly aware of its existence, until you try to communicate with someone with a different paradigm.”

As we pursue Transformational Learning, we need to have open and explicit conversations about what we mean by LEARNING before we get into the myriad other topics about how school works, and then continue to have conversations as we experiment with and reflect on new practices. Educators need to get these conversations about learning out in the open, in safe and collegial spaces, where we can reflect on and inquire into these ideas more deeply.

The distinctions I’ve attempted to spell out matter, and trying to communicate across these two very different mental models for learning just doesn’t work. If, in the course of our efforts to better serve kids and communities, these specific conversations about learning go unsaid, then we’ll continue to find ourselves viewing school through different panes of glass, fully unaware of what the other is really talking about.

“For apart from inquiry, apart from the praxis, individuals cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through invention and re-invention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other.” (Freire, 1972, p. 53)

References

I highly recommend 228 Accelerator’s Design Achievement at the Margins course, which led me to some of the resources that guided my thinking.

Butler-Mokoro, Shannon A., “Racial Uplift and Self-Determination: The African Methodist Episcopal Church and its Pursuit of Higher Education.” Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2010. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/eps_diss/64

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Penguin Education.

Haberman, M. (1991, December 1). The Pedagogy of Poverty Versus Good Teaching. Retrieved April 06, 2021, from https://kappanonline.org/the-pedagogy-of-poverty-versus-good-teaching/

Hattie, J. A., & Donoghue, G. M. (2016). Learning strategies: A synthesis and conceptual model. Npj Science of Learning, 1(1). doi:10.1038/npjscilearn.2016.13

McGee Banks, C. A., & Banks, J. (1995). Equity Pedagogy: An Essential Component of Multicultural Education. Theory Into Practice, 34(3), 152-158. Retrieved April 6, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1476634

Muhammad, G. (2020). Cultivating Genius: An Equity Framework for Culturally and Historically Responsive Literacy. Scholastic.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). How People Learn II: Learners, Contexts, and Cultures. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi: https://doi.org/10.17226/24783.

Nelson, S., & Williams, M. (Directors). (2018, February 19). Tell Them We Are Rising: The story of Black colleges and universities [Video file]. Retrieved April 6, 2021, from https://www.pbs.org/independentlens/films/tell-them-we-are-rising/

Noguera, Pedro, Linda Darling-Hammond, & Diane Friedlaender. 2015. Equal Opportunity for Deeper Learning. Students at the Center: Deeper Learning Research Series. Boston, MA: Jobs for the Future.

Perry, T. (1993, February 28). Toward a Theory of African American School Achievement. Report No. 16. Retrieved April 06, 2021, from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED366418

Senge, P., Roberts, C., Ross, R. B., Smith, B., & Kelner, A. (2009). The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization. London: Nicholas Brealey.